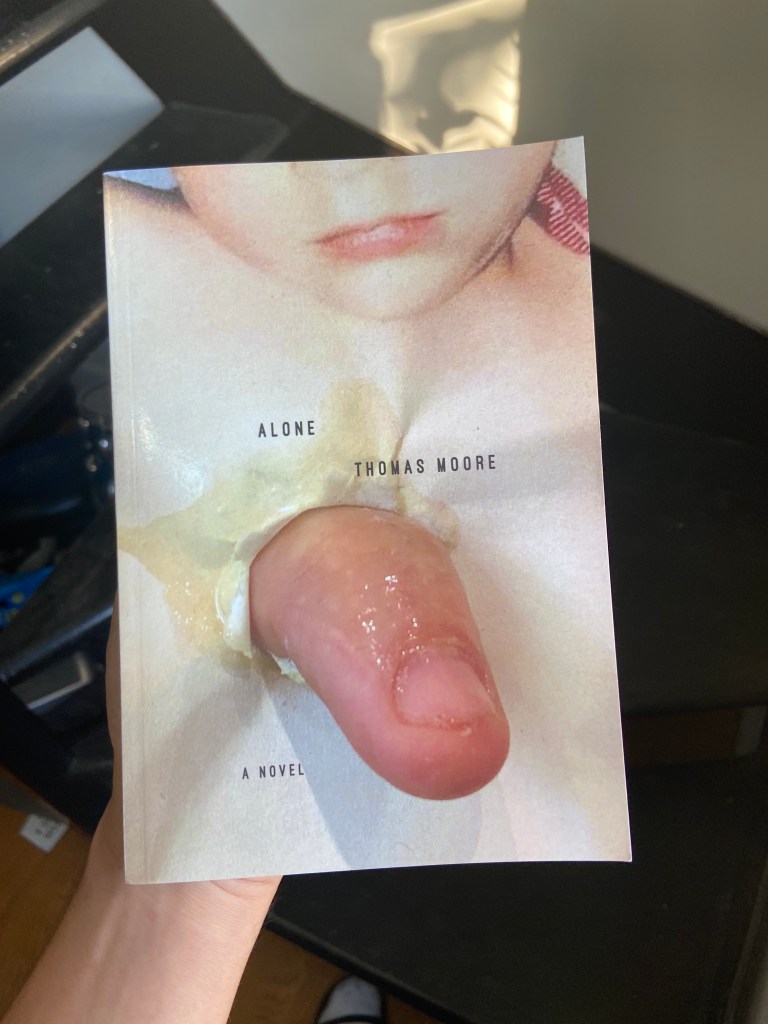

ALONE: A NOVEL by Thomas Moore, Amphetamine Sulphate 2020

I feel like I was hardwired for abandonment. It’s not as tragic as it might sound. If a person understands things about themselves and can be honest with themselves about it, then a lot of life’s pain is much more easily dealt with–pain, no matter how people try to fool themselves, or no matter how other people try and fool them–is never going to leave. The idea of happiness as a goal rather than a transitional state is a dangerous and much more damaging notion for a person to carry around than just knowing that each and everyone is fucked in some way or other. If you can admit that, then at least you’re able to recognise when you’re outside of the worst of it, those moments when you’re able to dance amidst the ashes.

What hit me repeatedly with this breathtaking short book by Thomas Moore is its agonizing clarity. These thoughts are so raw, so painful, and perfectly formulated.

The type is set so that there are hardly more than ten syllables per line of text–like a poem, practically. The rhythm is pounding in a fantastic way. I read this in one day.

There is no belief in love or lasting happiness; this is beyond cynicism about love (“I’ve never seen a relationship that I have envied”), but pessimism (Schopenhauer, also Nietzsche and Bataille) that is so present in this trend of gay literature:

I sometimes feel like I really hate language. As in I detest it. Language is a lie that we are all guilty of and have told so many times that most of the time we either believe it or are too tired to be able to fight off–I think it’s the latter.

As the narrator points out, “It’s drilled into people’s beliefs that they need to be with someone It’s the goal in children’s fairy tales, it’s encouraged by the state, it’s portrayed as the norm in the arts in the majority of places that you look.” So here is one place to talk about being alone, powerless, and suicidal, without fear. Loved it.

EEG by Daša Drndić, tr. Celia Hawkensworth, New Directions 2019

Ok, the comparisons between Drndić and Bolaño made regarding this novel are apt, I must say. In fact, EEG read to me as a conscious fusion of Bolaño and Sebald–a sure winner for international publishing. While I wasn’t blown away enough to want to check out the prequel to this work or the rest of the late Drndić’s corpus right away, this is definitely a vibe: B’s political nihilism, dread and despair; plus S’s generous inclusion of multiple individual narratives (though here coming through a prickly first person narrator).

It begins with a failed suicide on the surface, and it also launches this recurring image of congealing and concentration, of the horrific history of 20th century central Europe (one of its many long-standing conflicts suddenly and violently erupting at the end of September) into something formless.

I moved away to study small dead things, to observe close-up dead things that refuse to die. Arranged in impenetrable cages of milky glass, seen from outside, those dead things appear like quivering figures, opaque and inaudible. So, on my short journeys, I observed those huge cages, approached them, tapped on them, placed my hand on them to summon those imprisoned within, in case they came close to me, so I could speak to them through that thick milky-white glass, tell them I knew them, those imprisoned people, that I remembered their stories, that I was guarding their lives, but they just danced blissfully, disembodied in the silent vacuum. I remained invisible to them, external.

The book is a loosely structured album of these “short journeys” through Europe, documenting historical crimes at the ground level. It’s a grim diary of classical fascism. Genocide, racism, anti-Semitism, small national chauvinisms, as well as an angst over globalization. It is a petty-bourgeois intellectual’s cry against authority as such, against the philistinism of the middle classes.

Like Sebald, there is a ton of historical reporting that reads as non-fiction, as well as some photographs and a huge spreadsheet. The major highlight for me is the long passage on chess grandmasters who had all gone mad, which had a wonderful Lovecraftian feel.

What strikes me about this novel now is that the narrator, by piecing the story together this way for us, is committed, perhaps in a cynical or resigned way, to the Hegelian and even Marxist-Leninist idea of the absolute truth as a compound of many relative truths (the many stories of victims of multiple Nazi holocausts and national wars). The anti-fascist left in academia here in West, seems to me, would be more eager to reject Hegel and the dialectic out of hand as totalitarian or, more fashionable these days, a will to transparency. Not that EEG is a totality, even in the conscious design of its form, but it reads like an articulated attempt, out of a generosity to the victims of fascims and imperialism. The contemporary middle European writers, like Dubravka Ugrešić and Gaspodinov, just have a refreshing and infinitely nuanced view of this subject matter. These kinds of experiences, the collectively endured trauma, makes history seem to hang over everything, and it weighs heavy.

…the previous century and this one had coalesced, adhered in a squashy mass, which, like a half-dead, distended wild beast, at times powerful, at times in a state of decay, wafts around itself the stench of death and madness.

THE MAGICIAN by Christopher Zeischegg, Amphetamine Sulphate 2020

The best American novel of 2020 may be this beautiful and thrilling piece of transgressive literature from Zeischegg. I want to order everything else he’s written. THE MAGICIAN is a multimedia project with an awesome crescent-based logo (kind of like the one for DUNE), including a film—and to think that some of the events in this story will be staged is mind-shattering. The first 100 pages are raw and brutal, like 21st century Marquis de Sade. There’s a sequence that I can’t think of anything to compare with other than A SERBIAN FILM, except of course this is a prose novel so it goes directly into the mind. Then the supernatural elements and surrealism build up, layer by layer. There’s quietude and dread, adn a rhythmic prose that just rips you through the narrative. “I’d run out of small distractions. There was only the sound of crickets and whatever my body conjured up.” I’m going to be vague here. But the slogan I gave my IG post was that this experience is like an LA noir on benzos, unsparing yet deeply sensitive. The ending is devastating, and not in the way I was expecting.