To begin with, I’m not a physicist or natural scientist. Math was a struggle for most of my education. But I have been fascinated by theoretical physics since I watched some documentaries on public TV. It was the education I was missing in middle school. I loved the marvels it described, proliferating dopplegangers, objects phasing through walls. I thought science was justifying surrealism. –At least, quantum mechanics could be surrealistic in its implications, with the infinite degrees of freedom in a finite quantum field.

The lockdown in 2020 reawakened this fixation, with the help of the Sixty Symbols YouTube channel and in particular the work of Sean Carroll, who has quickly become my science communicator of choice.

In the decades since I watched those documentaries, I’ve received a decent amount of philosophical training. And looking back on my (superficial, popularized) learning in physics, so much of the ideological and theoretical commitments I hold to are corroborated by this very scientific field that has left so many professionals baffled and in need of positivism, pragmatism, and straight up metaphysics to cope with what quantum mechanics is telling us about the universe, namely that it’s a single, smoothly evolving wave function.

I listened to these professional physicists talk about the history of their own field, and it got me thinking about revolutionary history. It’s popular to believe that rigorous science can only be applied to the natural sciences specifically, while a science of society is impossible. The name of that science of society traditionally is Marxism. Marxism has no business calling itself a science, people say. But the history of the Communist movement has been and is a history of line struggles within Communist Parties, and of social revolutions, in which various state systems were torn down and new ones organized, and class modes of production were consciously surpassed. What about physics? There too is a history of revolutions, of one paradigm overthrowing another, of line struggles over fundamental questions about quantum mechanics, entropy, the arrow of time, the origins of spacetime, and so on.

In this video for the Sixty Symbols channel Carroll talks about how there is no winning majority framework theory of quantum mechanics. The plurality goes to the Copenhagen interpretation, but against the yardstick of philosophical materialism, this is actually an agnostic position: the physical reality of particles only exists when we are looking at them?? This is a pragmatist orientation to science, an orientation that says that the math in quantum physics (the Schrödinger equation) is only a practical recipe to help our endeavors in approximating a “ghostly” matter, rather than taking mathematics to be the theoretical reflection of reality’s basic fabric.

The interpretation that Carroll puts forward is the Everettian or “many worlds” framework, which, I learn in his book SOMETHING DEEPLY HIDDEN, is simply the “austere” form of quantum mechanics, the one that takes up the math as it is without any more tweaking (he quips that it’s the other interpretations that should be considered “disappearing worlds” theories). Not only is Carroll’s position in my mind the most consistently materialist, but there is also contradiction (i.e., dialectical reasoning) at work in his very prose:

You know who didn’t like the probability interpretation of the Schrödinger equation? Schrödinger himself. His goal, like Einstein’s, was to provide a definite mechanistic underpinning for quantum phenomena, not just to create a tool that could be used to calculate probabilities [emphasis mine]. “I don’t like it, and I’m sorry I ever had anything to do with it,” he later groused. The point of the famous Schrödinger’s Cat thought experiment, in which the wave function of a cat evolves (via the Schrödinger equation) into a superposition of “alive” and “dead,” was not to make people say, “Wow, quantum mechanics is really mysterious.” It was to make people say, “Wow, this can’t possibly be correct.” But to the best of our current knowledge, it is. (66)

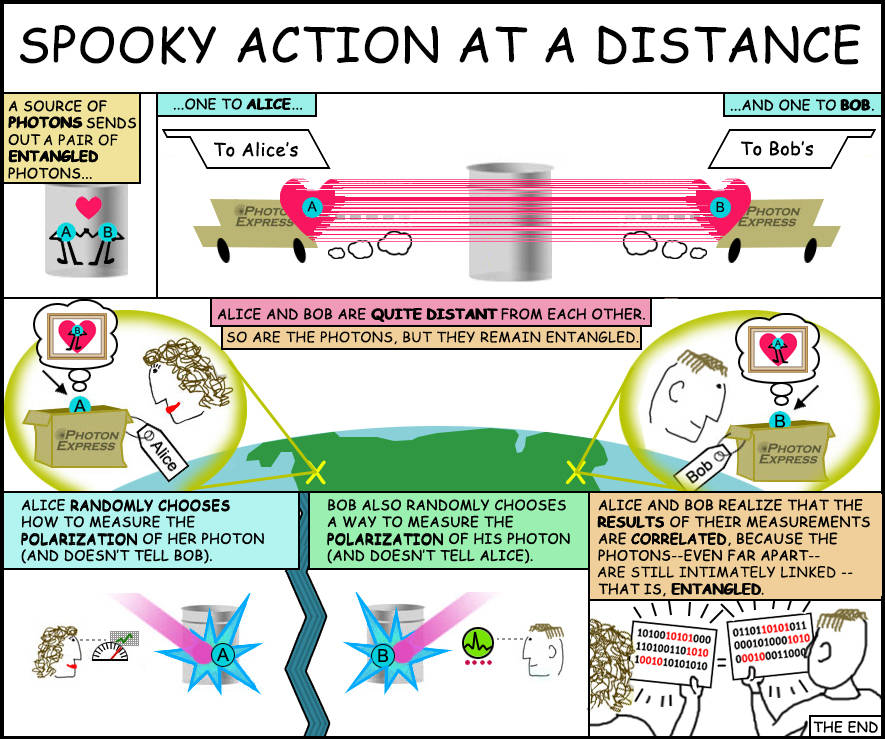

The apparent strangeness of what quantum mechanics describes about reality’s fundamentals has been an occasion for many to disregard the materialist outlook and keep the door open for New Age and metaphysical explanations for reality, with a whole subset of literature applying “entanglement” and other concepts in kooky ways, usually just a fancy way to talk about “Karma.” It is similar to the situation in the nineteenth century, when the mysteries of electromagnetism led some positivistic circles in Europe’s scientific community to abandon “naive” realism and claim reality was made of mathematical approximations. A certain author known in the indie circles has made much of the fact that the quantum theory of gravity is incomplete, and voices skepticism against Einstein’s general relativity. Are these people right? Does the framework of quantum mechanics justify idealism, subjectivism, and agnosticism? Is it the intervention of the observing consciousness that brings the variables of particles into existence?

So, is the weirdness of the quantum measurement process sufficiently intractable that we should discard physicalism itself, in favor of an idealistic philosophy that takes mind as the primary ground of reality? Does quantum mechanics necessarily imply the centrality of the mental?

No. We don’t need to invoke any special role for consciousness in order to address the quantum measurement problem. We’ve seen several counterexamples. Many-Worlds is an explicit example, accounting for the apparent collapse of the wave function using the purely mechanistic process of decoherence and branching. We’re allowed to contemplate the possibility that consciousness is somehow involved, but it’s just as certainly not forced on us by anything we currently understand. (224)

The only reason why our minds have anything to do with these processes is because we implicate our conscious experiences when we “map the quantum formalism” onto the world as we experience it. Science is indeed a subjective activity in this sense, in explaining conscious experience to ourselves, and reflecting the natural world and its structures in our minds, in the form of logical concepts and mathematics. The universe is physical and exists independently of our consciousness.

As with electromagnetism and biological evolution, successes in science have historically been grounds for reactionary ideologies to gain traction. But we should not pass over the knowledge science has accumulated because general relativity hasn’t yet been reconciled with the quantum field theory of gravity, any more than the successes in physics and chemistry in the late nineteenth century justified passing over physical matter entirely.

Carroll is not merely a brilliant working scientist but a great writer and communicator. His instinct for narrative served well (and his openness to storytelling technique as well as other humanities topics on his podcast is refreshing). SOMETHING DEEPLY HIDDEN is organized like a good quest plot of the Michael Moorcock type, where every new discovery promises to be the key to solving the next, greater riddle, like how a quantum theory of gravity becomes the key to unlocking the entropy of black holes.

So how is it that a mainstream branch of natural science is not necessarily naturalistic, or more precisely consistently materialist in the way other branches of natural science spontaneously are? Sean Carroll makes many polemical points, to the effect that bourgeois science is wilfully disinterested in the fundamental questions. The slogan, he says, is “Shut up and calculate.” But why should this be the case?

I think Sean Carroll answers the question in the YouTube video when he says the Copenhagen interpretation is “good enough for government work.”

In a word, it’s a matter of bourgeois society’s rampant utilitarianism. As advanced as technology has become, the capitalist mode of production can’t actually use science in the most complete way that is possible. I think with the global warming problem this issue has become transparent for a great deal of people in the last few years. Even more acute, perhaps, is the COVID situation where we see scientific expertise subsumed under the bourgeoisie’s “political expertise” at every turn.

Quantum mechanics, special relativity and general relativity, electromagnetism, theory of atoms—these are success stories of science that nevertheless, because they put a question mark over the structure of reality as it was then understood, prompted backward steps in philosophy and theory, birthing positivism (which tries to end philosophy altogether) and putting a question mark over matter itself. At this point who hasn’t seen a wise Twitter user “discover” for the zillionth time the “metaphysics” of dialectical materialism, because it posits a world independent of our first person experience of consciousness? Such a worldview allows me and I imagine the majority of the masses to move through the world just fine; it’s only the “progressive”philosophical postmodernists who take issue with such “naive” intuitions.

Actually, materialism is corroborated by the progress made in theoretical physics. Reality is much more contradictory and alive than the drab world of dead matter that the anti-materialist camp of Bataille and Deleuze and company (fashionable heroes for certain writers these days) are so fond of decrying. And a good thing, too.