Sometimes it be like that.

I’ve been giving up on novels at an above-average rate lately, tho it could be that my threshold for putting down a work of fiction is lowering.

It’s clear to me how well I’ve avoided writing about books here that I find unsatisfying. Talking about these experiences doesn’t come as easily.

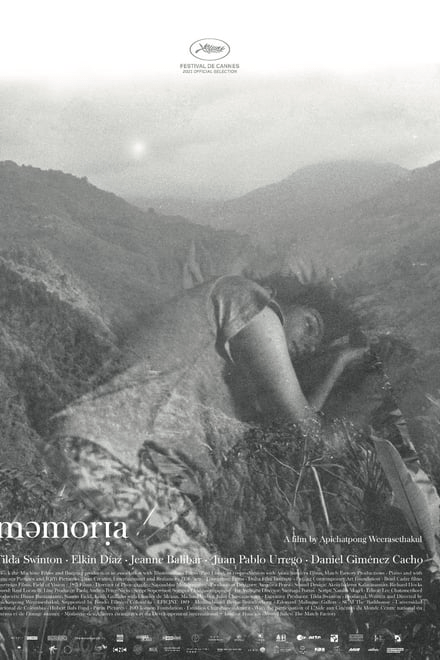

But on the other side are two positive things on the movie-going front. Really, going from EVERYTHING EVERYWHERE ALL AT ONCE by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert to MEMORIA by Apichatpong Weeresethekul was as hard a shift from maximalism to minimalism you could make within current narrative cinema.

It’s funny that a few posts back I had talked about quantum mechanics being surrealistic in its implications. Then in March mainstream audiences get nailed by a high-concept martial arts comedy whose conceit—fundamental it seems to a lot of Daniels’ work—is essentially a quasi-scientific rationalization for surrealism. Rather than subjective freedom of the imagination or the mysterious unconscious, this kind of goofiness is placed on an objective basis, with all matter being in a superposition of forms, and so on. However, the practical result is the same, for as Michelle Yeoh’s character says, you can imagine whatever nonsense you want and somewhere it is inevitably real. The absurdism may be too much for some audiences, and everyone will have a threshold at a different gag, but as someone who grew up on Stephen Chow I enjoyed this absurd hyperpop romp as produced by the Russo Bros. Stupid gags that are well thought out are the supreme form of comedy. The emotional core in the family drama was smartly written, especially at the beginning. The resolution was naive but one can appreciate the gesture against apathy and disappearing into the bagel/anus singularity, wrapped in a sci-fi concept that contains the noise of the multiverse as a reflection of the noise of the modern world. I can’t really think of anything else from the twenty-first century quite like it, except MINDGAME. And I have definitely never felt a crowd rocked so hard by a film in my life.

The fight scenes were fun to watch. There seemed to be a little bit of undercranking or a sped up quality to it, and there were things like the shot locked to the fanny pack rolling along the floor, reminiscent of Hong Kong movies. That’s the kind of over-the-top you want.

MEMORIA only sinks further beneath my skin with every passing day. On the one hand this was Weeresethekul’s epic breakout with international star Tilda Swinton in the lead, and dialog in English and Spanish. On the other hand, I found this to be the most starkly minimal film from the director yet. (I felt the length with this one, unlike with UNCLE BOONMEE or CEMETERY OF SPLENDOUR, though the running time is longer; the house was packed but the audience seemed to have a brutal time of it, unwilling to even shift in their seats, and when it ended we left in a pall of silence and existential dread.) UNCLE BOONMEE in comparison shares a lot about the characters’ subjectivities and their relationships to the setting. But we have to infer everything and anything about Swinton’s character Jessica, an expat living in Medellín, Colombia, visiting her sister in Bogotá who is recovering in the hospital at the national university. Of course the point is that Jessica is in a strange land, and with a sense of place denied, it’s as if her background and such becomes lost as well.

On a biographical note, I used to experience the same thing Jessica does in MEMORIA’s opening scene that kicks off her quest, namely exploding head syndrome, a sudden loud bang “heard” while falling asleep or waking up, not a real sound in the air but in the mind. This occurred to me semi-frequently when I was younger, up to the end of my teenage years. The “sound,” or the mental image of a sound, for me, was sometimes a dry thud similar to the sound effect in the movie, but it was more often a tinnitus-inducing schwing of a blade, or the pop of an electrical signal. Does Jessica’s bang really exist, as a memory or a premonition? Is it the same thing that’s setting off all the car alarms outside in the morning?

The best point for restricting this film to the theatrical experience is the use of sound, the climax of the film is essentially a grand formal experiment where sounds from other worlds fill the present moment, and then the soundtrack to the reality of the world eerily drops away. In one scene Jessica walks into a music session, a sequence done in three shots: her approach in the hallway, her watching the performance, and a reverse shot of the musicians. There’s time to dwell on hearing without seeing, then seeing and hearing, and the interactions of the performers were great. I distinctly remember a moment between the pianist and guitarist. The piece itself was a cool and worldly jazz fusion tune, very well chosen, the driving 6/8 time echoing Jessica’s odyssey.

I won’t spoil anything, for this is a decisively rare film to see, but there is a solution to the cause of the sound. After so many decades of art narratives sustaining ambiguity, perhaps explaining the mysteries of the world has become a bold step. With A.W. ‘s work in general, it seems that the story, in the moment of its experience, jerks suddenly into the realm of speculative fiction, but in retrospect you can see the atmosphere of science fiction enveloping all of his art.

E. H. Carr is a big name in my reading solely as the author of a monumental, multi-volume history of the Soviet Union up to 1930, with the initial trilogy of volumes on the Bolshevik Revolution being his headlining achievement. I’ve only gotten through a volume and a half—each book is around 600 pages of small print—but Carr’s excellence as a writer is certainly felt.

But if you listen to the national security punditry, Carr is also important in the space of international relations theory, and his book THE TWENTY YEARS’ CRISIS is considered a founding text for the twentieth century realist school in bourgeois political science. In its immediate context, the book was an argument for appeasement as the realistic policy choice (this was in 1939). While this is early on in Carr’s intellectual career and his grasp of Marxism remains superficial, his strengths as a prose stylist are well established. He delivers his argument in punchy lines such as: “the fact that utopian dishes prepared during these years at Geneva proved unpalatable to most of the principal governments concerned was a symptom of the growing divorce between theory and practice.” But underneath the rational presentation is a rather eclectic approach to diplomacy and the relations of forces at play in geopolitics.

The book’s ultimate result is a general description of the imperialist struggle of the great powers over spheres of influence. And this rough picture is colored by a bourgeois liberal perspective that is rather platitudinous. The theory of international relations is a simple spectrum between the poles of Utopianism and Realism, between argumentation based on the “common feeling of rights” and argumentation based on the “mechanical adjustment to changes” in geopolitical relations of forces. This balance is expressed concretely in the policy choices of Force or Appeasement. The fundamental problem of handling political change in the international sphere is that of a “compromise between power and morality.” Utopianism ignores power, Realism ignores morality. It becomes clear we’re in the liberal space of politics, since the ideal is nonviolent change (revolution is just as “immoral” as repression in the name of the status quo) and harmonization of class interests within each nation as well as a harmony of nations. But Carr’s critique of utopianism underscores how some overarching world system, either juridical or legislative, will never get off the ground as an adequate solution to the violent wars that keep erupting between competing monopoly blocs. These schemes did not reflect the material reality of international relations so much as the depression-era interests of engineers and technocratic intellectuals.

I ended up liking Hamaguchi’s adaptation of DRIVE MY CAR a lot, especially the low-key feelings it left me with at the end. It was enough to get me to try a Murakami novel out for myself, and I had a very used paperback of 1Q84 sitting around. This is a trilogy of science fiction novels, but I doubt I’ll make it more than halfway through the first volume, where my reading is currently sputtering out before a likely death.

Perhaps it doesn’t help that the book cross-cuts between two narrative lines, one involving a young woman on a mission named Aomame, and the other centered on Tengo, an up and coming writer who gets involved in an odd literary scam with his friend and a precocious teenager. It would clearly be many many pages before these lines converged.

Something about this prose makes it unpleasant to read yet just adequately interesting enough to keep me going. It is not repellant yet nothing attracts me to continue except I guess for its own ease of reading. Tragically, I keep opening the book again to give it another chance only to put it down after a couple pages, repeat ad nauseum.

I don’t enjoy inhabiting the characters’ worlds. What Tengo thinks about and the way he thinks about it stultifies me. These meandering thoughts in cafes, train stations, and bars sound more attractive than they are, like Katherine Mansfield getting drinks with a medicated Dostoevsky in a stuffy bar. Aomame comes off a bit shallow, and a petulant weirdo. She’s an assassin, an ex-softball player, a fighter, but she doesn’t reflect on her own goals that much and her gifts are laboriously presented by the narrator.

The number of people who could deliver a kick to the balls with Aomame’s mastery must have been few indeed. She had studied kick patterns with great diligence and never missed her daily practice. In kicking the balls, the most important thing was never to hesitate. One had to deliver a lightning attack to the adversary’s weakest point and do so mercilessly and with the utmost ferocity—just as when Hitler easily brought down France by striking at the weak point of the Maginot Line. One must not hesitate. A moment of indecision could be fatal.

Is this what fanfic readers refer to when they complain about a character being a Mary Sue? And what’s up with the favorable comparison to Hitler?

Perhaps this style serves to obscure the edge marking the alternate world that Aomame finds herself in, an alternative Tokyo 1984, which seems comfortably identical save for a few key details. This questionable 1984 is designated 1Q84 by Aomame.

Update: Murakami abandoned. Now reading violent American horror novels.