Read in November: Nesbo’s THE LEOPARD (much more violent, and more of a whodunnit than the dark motive-searching of Snowman; I’m glad Nesbo is willing to mix it up in this series) | Ashbery’s WAKEFULNESS.

António Lobo Antunes’s THE LAND AT THE END OF THE WORLD

An early book that has Lobo Antunes channeling Malcolm Lowry—and to better effect, since unfortunately I find UNDER THE VOLCANO disappointing in some respects (haven’t finished it yet). It’s hard to put a word on the fault I find with it, but it’s obscure. Even though the writing is clear for the most part, though it does slur in its rhythm. The novel’s landscape and characters remain shadowy from start to finish. Whenever we’re in the Consul’s point of view a kind of deranged yet pure-hearted and idle wordplay takes up the foreground, a semantic drift that serves as a kind of touchstone of the shitfaced: katzenjammer becomes cat’s pajamas, katabasis into cat’s abysses, then Cathartes atratus and so on.

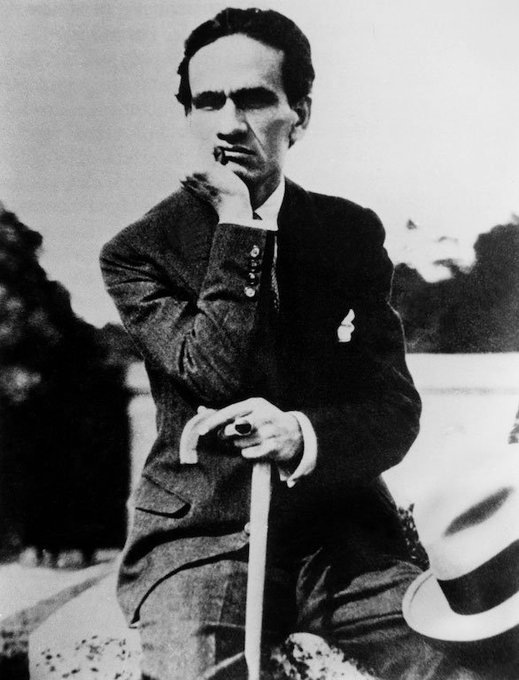

Vallejo’s AGAINST PROFESSIONAL SECRETS

This is a wonderful collection of prose pieces and notes. There’s such whimsy coming round the edges of these aphoristic constructions.

Cuando un órgano ejerce su función con plenitud, no hay malicia posible en el cuerpo. En el momento en que el tenista lanza magistralmente su bola, le posee una inocencia totalmente animal.

Lo mismo ocurre con el cerebro. En el momento en que el filósofo sorprende una nueva verdad, es una bestia completa. Anatole France decía que el sentimiento religioso es la función de un órgano especial del cuerpo humano, hasta ahora desconocido. Podría también afirmarse que, en el momento preciso en que este órgano de la funciona con plenitud, el creyente es también un ser desprovisto a tal punto de malicia que se diría un perfecto animal.

(When an organ carries out its function fully, there is no possible malice in the body. At the moment a tennis player masterfully tosses the ball, he is possessed by animal innocence.

The same occurs within the brain. At the moment the philosopher discovers a new truth, he is a complete beast. Anatole France said that religious sentiment is the function of a special organ of the human body, yet to be discovered. One could also affirm that, at the precise moment that this organ of faith functions at its peak, the believer is also a being so devoid of malice that he could be called utterly animal.)

I had a reading of these lines, but my booster shot for the Covid vaccine obliterated it, so that I can no longer understand what I had thought.

Vallejo is someone you want to follow as a disciple, what a scary authoritative presence. This book includes fragments from his notebooks, and just the single mention of Knut Hamsun compels me to put him at the top of the TBR. Also: “El arte según Marx: reflejo de la economía (Art according to Marx: reflection of the economy).” And “Poetas según Marx, que deben ser políticos militantes y conocerlo y vivirlo todo (Poets according to Marx, should be militant politicians who know it all and live it all).”

Lately I’ve been thinking about the opening shot of SICARIO, where the federal troops creep into a view of suburban America. A story I once read in PLOUGHSHARES (I can’t seem to locate it) opens with a similar image, armed cops on the rooftop of a family home to stop a mass shooter. The same vibe is achieved in THE GHOST SOLDIERS by James Tate, a poetry collection that creates the impression that all these pieces take place in the same small town in the Midwest that is constantly disrupted by warfare, with bombs landing in cow pastures and tanks blowing away farm houses. I’m increasingly drawn to this conceit of massive, mechanized violence brought to bear on safe and idyllic places where such things aren’t supposed to happen, but of course the comfort of the latter rests on the former taking place elsewhere.

The first 30 pages of WAR OF THE WORLDS makes this point again, as ground zero for the Martian invasion is the peaceful northern London suburb of Barnet. A Sci-fi war bursts into a scene of bourgeois domestic bliss:

About six in the evening, as I sat at tea with my wife in the summerhouse talking vigorously about the battle that was lowering upon us, I heard a muffled detonation from the common, and immediately after a gust of firing. Close on the heels of that came a violent rattling crash, quite close to us, that shook the ground; and, starting out upon the lawn, I saw the tops of the trees about the Oriental College burst into smoky red flame, and the tower of the little church beside it slide down into ruin. The pinnacle of the mosque had vanished, and the roof line of the college itself looked as if a hundred-ton gun had been at work upon it. One of our chimneys cracked as if a shot had hit it, flew, and a piece of it came clattering down the tiles and made a heap of broken red fragments upon the flower bed by my study window.

I’m pretty sure the first time I read this book was shortly before 9/11, and perhaps the longer you wait before a reread, the more empowering it may feel. It goes by fast. I was moved to revisit it by the 83rd anniversary of Welles’s radio broadcast last Halloween weekend. And to my surprise the modern film and TV adaptations are pretty faithful to Wells’s original plot, but with faster pacing and other adornments.

Unfortunately I seemed to have entered a trough toward the end of November, and in the middle of producing this post, I have forgotten how to read and write.